About Lucretia Coffin Mott

Lucretia Coffin Mott

Chronology

| Lucretia Coffin Mott (hereafter LCM) was born on January 3, 1793, to

Quaker parents in the seaport town of Nantucket, Massachusetts. When

she was 13, the Coffins decided to send Lucretia to a co-educational Quaker

school, Nine Partners, in Dutchess County, New York. It was here

that Lucretia met James Mott. From 1808-10 she served as an assistant

teacher at Nine Partners, and during that time the Coffin family moved

from Boston to Philadelphia, a city that was to be Lucretia's home for

the rest of her life.

In 1811 James Mott and Lucretia Coffin married, and he engaged in cotton

and wool trade (he later focused only on wool trading as a protest against

the slavery-dependent cotton industry in the South). Between 1812

and 1828 Mott bore six children, of whom five lived to adulthood.

She began to speak at Quaker meetings in 1818, and in 1821 she was recognized

as a minister in the Society of Friends in Philadelphia. |

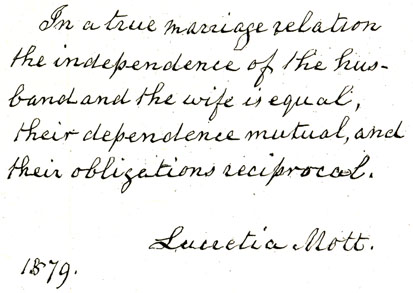

Courtesy of the Mott Collection, Friends Historical Library,

Swarthmore College |

Throughout their long marriage James Mott encouraged his wife in her

many activities outside the home. The Quaker tradition enabled women

to take public positions on a variety of social problems and in the 1830s

Lucretia was elected as a clerk of the Philadelphia Women's Yearly Meeting.

During the 1820s a rift formed between the stricter, more conservative

Quakers and the tolerant, less orthodox followers of Elias Hicks (known

as the Hicksites). In 1827 first James and then Lucretia followed

the Hicksite branch which espoused free interpretation of the Bible and

reliance on inward, as opposed to historic Christian, guidance. Later

in her life, although remaining a Hicksite Quaker and appearing only in

simple, plain clothing, she often spoke in Unitarian churches; her sermons

show her full engagement in the liberal religious discussions of the day.

LCM's letters reflect her regular travels in the mid-nineteenth century

throughout the East and Midwest as she addressed various reform organizations

such as the Non-Resistance Society, the Anti-Slavery Convention of American

Women as well as the quarterly and yearly Quaker meetings.

Her letters not only express the thoughts of a public figure but they also

show the anxieties and joys of a nineteenth-century woman. Forceful and

intelligent, her letters also reflect Mott's character and Quaker

background.

LCM's only trip abroad occurred in 1840. Chosen as one of six

women delegates from the several American antislavery societies to the

World's Anti-Slavery Convention, she and James Mott sailed for England

on May 5. On June 12, she and the other women delegates were refused

seats, despite the protest of other Americans attending the convention

(such as William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips). At this conference

LCM met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Scholars agree about LCM's germinal

influence on Stanton's determination to seek equality for all women.

1848 witnessed the birth of the women's rights movement in the historic

Seneca Falls Convention which issued the women's Declaration of Sentiments,

a call for equal treatment of women. LCM presided over the Seneca

Falls meeting and was the first to sign the Declaration. Until her

death, LCM remained a leader in women's rights organizations. [Link to letter to

Elizabeth Cady Stanton]

Throughout the turbulent 1850s, LCM continued her speaking and engaged

in further antislavery and non-resistant activities. She worked with

other antislavery leaders such as Frederick

Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Lucy Stone. As a Quaker

preaching non-violence, LCM denounced the Civil War but not without some

conflict, for, like other antislavery activists, she hoped the war would

end slavery.

In recognition of her long service to the women's rights cause she was

chosen first president of the Equal Rights Association in May 1866.

Ever the peacemaker, LCM tried to heal the breach between Elizabeth Cady

Stanton/Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone over the immediate goal of the

women's movement: suffrage for freedmen and all women? or suffrage for

freedmen first? In the Selected Letters, LCM's private views on this

split are available for the first time.

In her 85th year LCM delivered her last public address when women's

rights advocates celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Seneca Falls convention

in Rochester. Throughout her life, an incisive, challenging mind,

a clear sense of her mission, and a level-headed personality made

her a natural leader and a major force in nineteenth-century American life.

Back to Mott Home

Page